By: Alex M. Lehmann

Art Director, Riot Games

Almost seven years ago I transitioned from animating for commercials and feature film over to games. I was always a huge gamer, but never pictured myself creating games myself… until the day I started at a (then) small, scrappy company called “Riot Games” in an art team of 6. I created my first run cycle on a character named “Nidalee”. After seeing her come to life in game, I was completely hooked. I had found my calling. Riot’s growth since then has been an incredible ride, and so was my personal growth.

Little did I know that there are many subtle and important differences between working in games and feature film… and I had to learn them the hard way. Below is a list of things I wish I had known when I originally started out. Hopefully there’s something in here for you to start a successful and fulfilling career in video games.

1. You are a game developer first and animator second

Yeah, to some this is a hard pill to swallow and to others this is exciting. Being an animator in games is “more” than just animation. The animation you create serves not only an emotional goal, or a narrative, but far more often the game mechanics that drive the overall gameplay experience. And that’s not all of it.

Riot’s Thunderdome event let’s artists, engineers, designers etc. work on “anything they want to create” within 3 days. It’s the ultimate form of cross-discipline collaboration and requires a “game developer”-mindset.

More than in other industries I’ve worked with you’ll be embedded in a cross-discipline team with designers, engineers, VFX artists, audio engineers, tech and 3D artists, concept etc. Most likely you’ll get together on a daily basis to figure out what to work on next to create something amazing for your players. You’ll have to solve technical problems, understand the game, know the basics of what makes something fun, communicate on a daily basis, play other companies’ games for research, and stay up-to-date with the latest technology. If the outlook of an ever changing environment excites you, the games industry is for you. From moment to moment you will have to wear many hats, empathize with other disciplines’ needs, and learn to speak their language. In short, you’ll become a more holistic game developer the longer you work in such an environment.

2. Put it in the game

More than in other mediums, the quality of your animation doesn’t mean anything until you put it in the game to verify whether it’s actually “fun”. Something might have the tightest arcs, snappy timing, and feel great in a 30fps playblast, but once you see it in a top-down camera, with real-time lighting, and running compressed through multiple additive animation layers it just falls flat. When it comes to the craft aspect, my biggest and most important tip is this: work in the engine as much as possible.

See Rory Alderton’s animation below from this article demonstrating the difference between in-Maya animation and in-engine.

My personal preference is to quickly create a single pose that best describes the feeling for a character (for each animation/asset I have to work on) and immediately put that in the game. In as little as 2 days I often have a character switching pose to pose on a button press, immediately showing me whether I’m on the right track. The added bonus is that changing anything at this point is completely painless – and if you work in games you’ll get a ton of feedback from designers, VFX artists, audio engineers, or pretty much anyone working in the company. The best way to improve on a craft level in games: create animations within and for the engine and camera the player is using. Anything else runs the risk to serve only the art itself.

3. “Feel” is more important than visuals

Don’t get me wrong, visuals are very important. You should study hard and work tirelessly to make them as good as you can, but what really counts in the end is how it “feels” . That’s what we are aiming for in games. Get the controller out and run around, hit the button, and notice how it feels. How responsive is it? Does the animation do what you expect? Do you feel strong or weak, fast or slow? Do you feel in control? Once you identified how it “feels” make changes to improve your animation.

As I mentioned in a GDC talk “Tricks of the Trade” in 2016, at Riot we often put the anticipation of an animation at the end of the cycle. This makes the animations responsive and “feel good”, though it realistically doesn’t follow logic. In the end what matters is what happens in a player’s head – and if something is “fun” then it often is the right way to go.

This also means that realism, unless called for by the game, is not always your best ally. Want a punch to take 2 frames but last 1.5 seconds? Does it feel good? Then do it! It’s more about what feels right than what is “right”. Be bold and experiment… don’t get hung up with realism if your game doesn’t call for it. You’ll see you get away with way more things than you thought you could.

4. Get to know your pipeline well

If you start working in games, mastering Maya is only one of your hurdles. Most of the times you’ll work on one of the more common engines like Unreal, Unity, or CryEngine. At some studios, you may even have to learn the ins and outs of a proprietary engine. Take the time to understand compression algorithms and learn what a Hierarchical State Machine is. Get to know how to implement data without “crashing the build” (esp. on a live game like League of Legends) and which design hooks are necessary to trigger an animation. These skills outside of animation will be essential for you to be effective. So, think holistically when creating animations. Ask yourself who might be affected by this asset/change, and what is the smartest technical solution for any given asset.

And think of your tools. Ever bought a device which you only used 30% of the main functions of? I’m sure we all did. But when it comes to working smarter – not harder, knowing your tools is incredibly important. Get to know the tools you have. If your studio is small and is using “vanilla” Maya, read up on the latest developments and see if new features could help you do something smarter. Create hotkeys for some of the most common functions (like toggling visibility on NURBS curves and control objects).

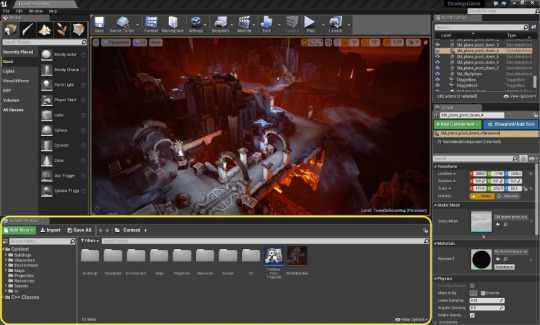

An image from Epic’s Unreal Engine 4 a powerful and deep tool requires months to learn and years to master

For example: I encounter a lot of animators that don’t use animation layers though they provide a fantastic way of creating additives or variants for your cycles. By understanding them and their limitations you’ll become a more effective animator able to provide ideas and unblock your team on a daily basis. And even if your engine doesn’t support them, could you maybe bake out animations right before export? Think outside of the box to make your life easier!

If you have a tech artist on your team, be sure to talk often and openly. Help them to create the pipeline and tools that make you more efficient and be appreciative of their time. Ask yourself if something can be automated. One of the hardest things for tech artists is to prioritize. TAs’ passion is to help artists and create efficiency – and there’s always something to fix. Be patient when necessary and provide any help you can for the tech artists so they can unblock you down the road.

5. Soft skills are just as important

When it comes to creating animations for games, there’s a ton to learn: the 3D software you work in, motion capture if the game asks for it, the engine you generate the assets for, gameplay and basic “design” skills… but most of all: working within a team.

Working on your soft skills is just as important as learning how to trace an arc or animate squash and stretch. Learn how to give and receive feedback, understand the whole pipeline start to finish, work on your empathy, don’t hide your faults, but openly work on them, be vulnerable, admit your mistakes, be gracious when others fail and generous with feedback and help… there are many soft skills that will make you a more valuable team member. If this interests you, there are a few books I highly recommend:

- Crucial Conversations

- 5 Dysfunctions of a team – how to become a great team member/leader (whether you are a leader or not)

- Mindset (Carol Dweck)

- Extreme Ownership

There’s so much more I could talk about, as the last couple of years have been an amazing ride. And yet, these are certainly five things that made a difference for me. Being an animator in the game industry can truly be the job of a lifetime. It requires a great team and lots of hard work and dedication on your end. The good news is that you have all the cards in your hand to grow and become better at it each day. I can’t wait to play future games that you all will be working on!

Stay in touch:

@alexmlehmann (Twitter)

Lx, “RiotCaptainLx” on League of Legends’ NA-Server